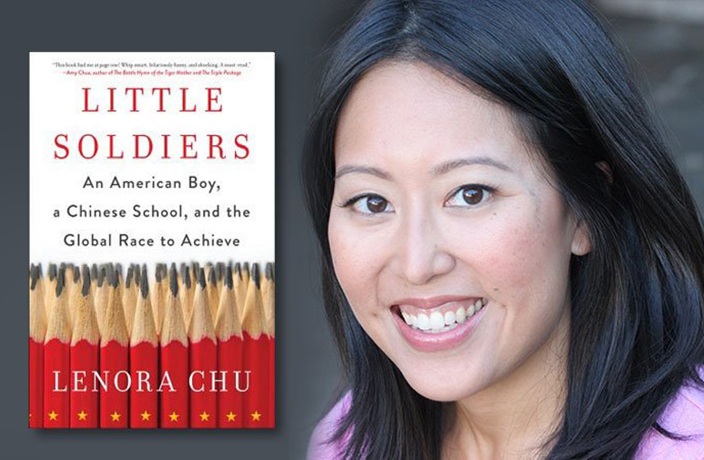

Most American families in China send their children to international schools. Not Lenora Chu’s family. The Texas native and her husband moved to China the same year that international standardized testing ranked 15-year-olds in Shanghai the best at math in the world. Shortly after, Chu enrolled her son Rainey in one of the city’s most prestigious Chinese kindergartens, Soong Qing Ling. And it was... a shock, as Chu writes in the introduction to her book on the subject, Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School and the Global Race to Achieve.

But Little Soldiers is more than a memoir – it’s a refreshingly nuanced look at the differences between the Chinese and American education systems. A journalist, Chu chronicles not only her own family’s experiences, but also follows Chinese high schoolers, both rich and poor, as they prepare for the notorious gaokao (college entrance exams).

We sat down with Chu to learn more:

What led you to write this book?

It’s funny – before, it was supposed to be a different book. I worked for seven years in LA, in acting and writing, and I had been working on a book dealing with those things. But when my son began taking classes in Shanghai, I was struck with just how much more interesting a book about my son’s experiences would be than my own. So things just changed with the times. The story basically told itself.

Your book has made headlines all over the US. How are readers responding to it?

It depends. When I’m talking to Chinese parents, they generally want to understand what we’re doing in America, and how they can incorporate those things into their own lives. Yesterday I talked to a Chinese parent, who asked me simply, “How do you talk to your kids?” I explained that in the US, we like to create a safe space for a child to say what they feel and answer, or not answer, our questions. This was completely novel to this parent.

I’ve also heard Americans who work in education complain that their profession doesn’t receive the same sort of respect that it would here in China. And I had a guy from the US complain to me that the word ‘talent’ should be banned from American classrooms – he was told that he was talented as a kid, which resulted in never having to work very hard. But I’ve also essentially had the opposite told to me as well. It’s really all over the map.

Why did you choose to write about your family and other families, and how did you balance the two?

I have to say, it’s a gift that I’m a journalist, but in some ways it made the project more challenging. There are dual narratives. Because of my interest in journalism, and because I had Mandarin-language skills and access to classrooms, I would have felt ashamed if I had not properly researched and vetted my work like a reporter. My challenge was to weave between writing a book and writing a report in a way that was interesting to everyone. This is why the project took about a year and a half longer than anticipated!

Over the course of your reporting, what surprised you?

The private lives of the Chinese students I followed. One boy, Darcy, had a lot of secrets. He had a secret girlfriend. He had a secret mobile phone his dad didn’t know about. He was living two lives.

Chinese kids are taught obedience, and they’re taught to always submit to the authority of a teacher. This creates an atmosphere where the kids will keep to themselves more. In America, the kids that are leaders in a classroom are often simply the loudest, and here [in China], it’s almost always the opposite.

What misperceptions do Westerners have about the Chinese education system?

There is a narrative that Chinese youth are not outspoken and creative. Much of the insecurity stemming from Western education is based on standardized tests and various international measuring sticks, in which students in the UK and the US are not exactly exemplary. The narrative that Chinese students are not creative and self-sustaining helps us feel better.

How have fellow expat families in China responded to your work?

Many have told me that they were struggling with the very things I discuss in my book. One person I talked to told me I had helped their family make a decision about where they would send their kids.

What do you personally like best about each education system?

I like the signaling that goes on in a typical Chinese classroom. Children are taught from a very young age to always nod and say hello to a teacher. It’s a small thing, but many Western teachers have told me they’ll walk into their classroom, say ‘hi,’ and no one says anything back. So it’s a subtle gesture that reaffirms the importance of a teacher.

On the other hand, this can produce inflated egos. I’ve talked to [Chinese] teachers who shame students because they don’t draw rain the ‘correct way.’ It’s ultimately about finding a good balance.

What are some things you dislike about either system of education?

In China, in many ways, it’s a zero-sum game. In my book, I talk about how there are 18 million Chinese kids entering the system right now. Only about half of those will make it to a high school equivalent. China isn’t coming any closer to solving this problem.

At least in China, though, there is a general agreement on what the problems are. In the West, any particular criticism of education will be debated by both the political right and left. It’s an environment that isn’t as conducive to change.

Your book shows the upsides and downsides of both education systems. It comes across as a very even-handed look at the two. Do some people get frustrated that you’re not choosing a side?

I have my own perspective and my own thoughts, but I thought it would be important to give a more fair illustration. The reporter in me had to present my findings in a very objective and neutral manner.

Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School and the Global Race to Achieve is out via HarperCollins