"When my friends in [Chinese] public schools look at my maths homework, they’re amazed how easy it is; they can work out the solutions in seconds,” says 16-year-old Seline Wang, who’s studying for her IGCSEs at one of Shenzhen’s international schools.

Wang’s experience is indicative of the disparity in numeracy between China and England, a phenomenon that has consistently hit British headlines this year following a report released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The December 2013 OECD report revealed that children of cleaners in Shanghai outperform the children of doctors and lawyers in England in math; moreover, the children of unskilled parents in England are a whopping two-and-a-half years behind their Shanghainese counterparts.

Specifically, China (Shanghai), Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan sit attentively in the top four global seats according to OECD statistics compiled in 2012. English-speaking countries perform comparatively poorly: America snoozes at the back with its feet on the desk, ranking at 36, while its cousins seem to be awake but looking out of the window, picking their noses – Canada, Australia, Ireland and England saunter in at 13th, 19th, 20th and 26th respectively.

In fact, England and its reactionary media felt the math gap so acutely that UK Education Minister Liz Truss knee-jerked a response in early 2014. Her stroke of misguided genius? Ship in 60 teachers from China to show the bewildered youth of England the path to Pythagoras! Unfortunately political grandstanding in this manner fails to get to the cultural heart of the matter: why do Chinese students really perform better at math? Can Chinese methods be applied in the West? And – more abstractly – do superior math exam skills translate to GDP growth?

The gap in mathematical capabilities between some (but not all) Asian countries and English-speaking nations rests with a mix of parental expectations, cultural attitudes towards math and – to a minor extent – teaching methodologies. Rather than a genetic predisposition to math superiority, the above cultural factors combine into the core reason for Chinese students’ success: practice, practice and more practice.

In terms of what parents demand from their offspring, a clear gulf exists between East and West. Research by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) reveals that while American and Chinese fathers estimate similar scores in math for their children, “American parents, teachers and students hold markedly lower standards for academic achievement than do their counterparts in Asia.” In contrast, a 2014 study by sociologists Jennifer Lee and Zhou Min targeting Chinese and Vietnamese parents reveals that most Asian parents believe “A is for average and B is an Asian fail.”

Research by Hong Kong University analyzed the role of parents in math learning based on a survey comprising 198 students in Hangzhou. The study concluded that “parental expectations for their children and involvement in their children's mathematics learning were two major factors which influence children's educational expectations for themselves [and] attitudes toward mathematics.”

The attitude toward math in China, however, extends beyond pushy ‘tiger moms’ that force hardcore workloads on their kids. It embodies a cultural mindset about math and its role in education as a bridge to a better life. With experience in both Asia and Britain, Fan Langhuo, Professor of Education at the UK’s University of Southampton, believes that, “In China, all parents know that maths is the number one subject in schools… In Britain, students’ attitudes are different. They feel it's alright if they say they don’t like mathematics.”

In fact, cultural attitudes seem to be far more important in explaining performance disparity than exaggerated differences in teaching methodologies or genetic predisposition. USA Today cites the following findings from research in 2013: “The News-Press traveled this summer to Asia, where students – on paper – are running circles around American children, especially in math and science. Five countries and nearly 25,000 miles later, one revelation became clear: a math class there is the same as a math class here, only in a different language.”

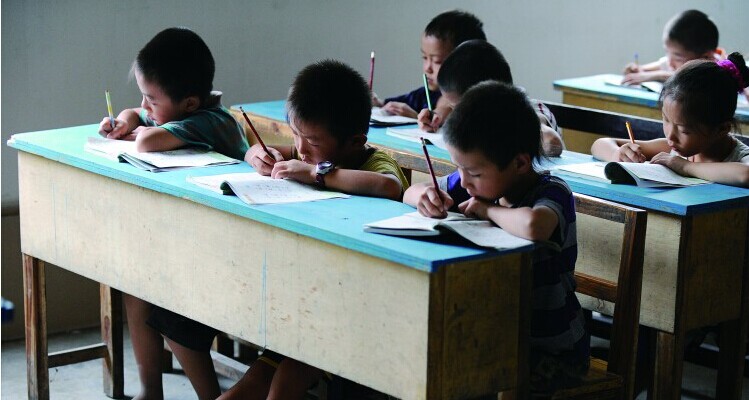

Pushed by their parents’, teachers’ and society’s expectations, Chinese students complete math homework ad nauseum and, in the process, rote-learn how to tackle exam questions. Public school student Tom Zhang, 16, tells us that the Chinese method has both drawbacks and strengths: “If you deviate from the way the teacher does things or suggest something new, teachers get annoyed. But learning in this way is very thorough and provides an excellent foundation for further study and branching out at university.”

IGCSE, a British-based curriculum, doesn’t seem that different – it just moves at a slower pace and so doesn’t get as advanced. Student Seline Wang feels it suits students who lack a natural affinity with math. “IGCSE suits me because it gives a better understanding of why a formula is used,” she says, “but it’s not as advanced as what students are learning in China’s public schools.”

Thus, the major difference between the curricula in China and – in this case – Britain seems to lie with aiming for gold rather than any innate racial capability. China teaches towards the high end of the class, which forces all students to raise their game and drives up exam scores. Conversely, England teaches towards the middle of the pack, if not the lower end. As OECD statistics and national attitudes seem to evidence, the UK approach decreases competition, makes it okay to go for bronze and leads to patchy assessment performance. For example, in April this year the British press praised the “high performance” of spectacular mediocrity when its students came in 11th in international problem-solving tests.

In terms of economic value, critics state that China’s outstanding math scores are part of the locally acknowledged ‘gaokao dineng’ equation – ‘high scores, low ability.’ In his article, ‘Why China isn’t a threat yet: The cost of high scores,’ educational writer Zhao Yang notes the importance of the “products of education,” which encompass attainments in life and work. Zhao expands on something he feels is missing in China: “The quality of education by school-related factors, such as test scores, should consistently predict the performance of school graduates in society.” He believes this is not the case because students’ paper abilities and the skills that industry actually requires are worlds apart.

Both England and America are guilty of glorifying China’s educational achievements; China to an extent does the same in reverse by positioning Western universities as the Holy Grail for its students.

In Britain’s case, importing 60 Chinese math teachers will not inspire the nation’s youth to start doing math homework till past midnight, change parental attitudes overnight or lead the government to recognize – as it did 30 years ago – the importance of rote-learning as a valuable tool for giving students a strong foundation.

In China’s case, an over-emphasis on rote-learning and exam results will continue to lead global league tables, but might not produce leading scientists, researchers or individuals that can look back on a happy school life while thriving in the work place.

In math, the differences in teaching methodologies and genetic predisposition between East and West are overplayed. It boils down to a case of hard work inspired by cultural and familial expectations intertwined with intense competition: Chinese students simply practice far more for exams and move through the curriculum much faster.

Regardless of which approach is better or leads to a more robust economy, if countries such as England continue to eschew rote-learning and take a softly-softly approach to schooling, China’s exam results will remain much higher.